:strip_icc()/pic3613423.png)

So, this is a review of both the Sentinels Comics RPG Starter Kit (see above) and the Sentinels Comics Core Rulebook. I picked up the Sentinels Comics RPG Starter Kit a number of years ago, but it sat unopened! It remained in shrink-wrap because I couldn’t find a group here in Tucson who was interested. So, when the main Sentinels Comics Core Rulebook (see below) went on Kickstarter, I had trouble justifying getting it because I still hadn’t opened the base game!

Luckily, I found a group to play! Right now, we are currently playing the Sentinels Comics RPG on Thursdays (over Discord) and it’s a blast! It’s a fun and easy RPG to get into. The Starter kit has premade characters and makes it VERY EASY to get into the base game! See below for one of the premade characters!

The character books describe in just a few pages how to play. I was impressed at how easy it was to get a character going! If you want to make your OWN characters, that’s what you need the main Core Rulebook for!

Sentinels Starter Kit? Easy to get going quickly. My friend CC, who has been GMing the game for us (and has the Core Rulebook) has played and run a lot more games of Sentinels Comics than myself, so I’ll let him take over!

Sentinels Comics Core Rulebook

The Sentinel Comics RPG Starter Kit came out in 2017. It showcased the core gameplay of this new superhero RPG system, included SIX adventures, and offered several beloved characters from a popular card game as playable heroes. Now, three years later, the core rulebook has finally been released. Has it been worth the wait (and the $60 price tag)?

I can say, unequivocally, YES.

Let’s look at this book from several perspectives:

Art

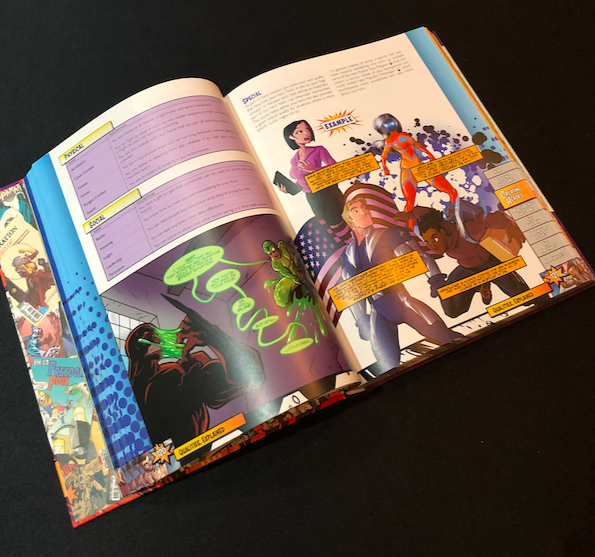

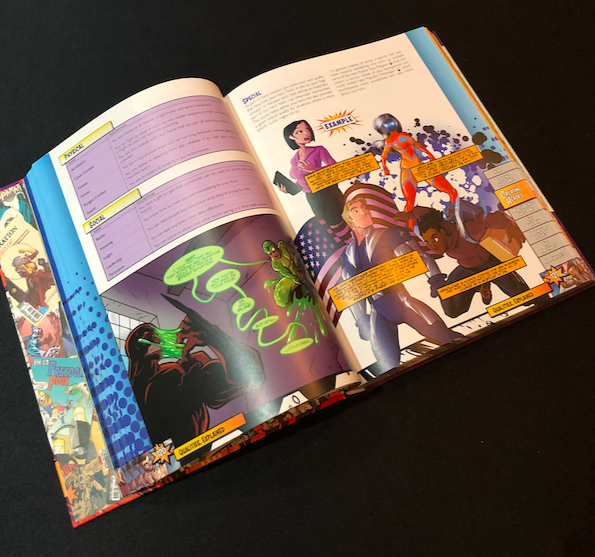

The Sentinel Comics RPG Core Rulebook is easily one of the most beautiful hardbound rulebooks I own, and I’ve owned many over the years. This book is a thing of beauty. Full-color superheroic illustrations from many artists, evoking comic panels from many genres, time periods, and art styles fill the book from cover to cover. Some pieces are better than others, naturally, but rare is the page that doesn’t have an evocative illustration of a hero looking heroic or a villain looking villainous. Greater Than Games did not skimp in this area, and it shows – the book is a pleasure just to flip through.

Graphic Design/Layout

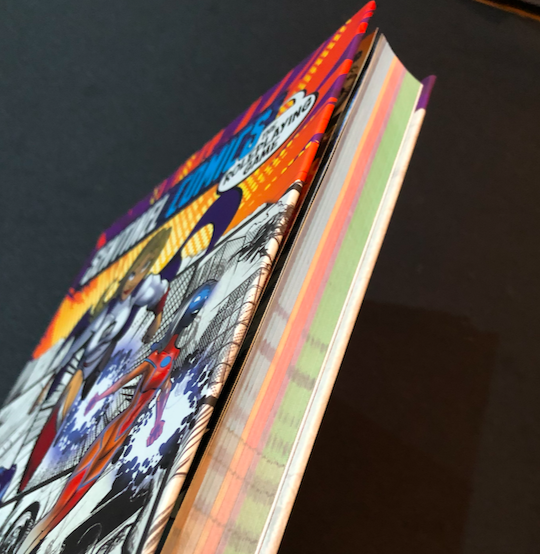

But what about the layout and presentation? There are a lot of great affordances in the layout of this book. One very clever element is the fact that each chapter is color-coded, and the edges of each page is tinted to the associated color. Not only does this make it very quick to find your way through the book when flipping through it, but you can also literally see the chapters when looking at the closed book from the side, allowing you to open the book very close to where you need to.

Another innovation I appreciated was in some rules presentations. Many of examples of game mechanics in action are provided, and not just inline in the text – instead, they are pulled out and illustrated as comic panels, where each player is speaking to each other with speech balloons, expressions, etc. This makes reading the rules a pleasure, and is very good at driving home the salient points of the rules. Another example of this is the character creation summary, which is, again, presented as a series of comic panels. The book is absolutely steeped in the theme, which drives excitement and brainstorming. My only gripe with the graphic design is that the body font chosen has a quite thin line weight which makes it slightly harder to read than it might otherwise be, but they chose a large enough font size for it that it’s not really an issue.

Content and Presentation

There is a LOT of content in this book. The book consists of six main chapters (plus an introduction, appendices, index, etc.). The first main chapter is “Playing the Game”, which contains a full summary of all the rules you need to run the game. The short version of this is that it’s solid, workable, and trim, but for more discussion on this, see Gameplay, below.

The next section is support for creating your own superheroes. This is almost certainly what a lot of players are looking forward to with this game, and it doesn’t disappoint. There are three methods presented for creating a character – a “guided” method, a “constructed” method, and a “secret third option”. The guided method is for players who don’t have an idea of the hero they want to play yet, and it prompts them to roll dice to suggest options. What’s really clever about this is that it doesn’t just assign the hero as you go; instead, it’s more of a rubric for giving players a few options to choose from at each step. I’ve made some really fun heroes with this method, creating cool concepts on the fly.

For players who have a concept for the character they want, there’s the “constructed” method. It uses the exact same system that the “guided” method does – the only difference is that instead of rolling to get some options, you just, basically, choose the option you want. Simple, straightforward, and entirely compatible with the other method.

The third “secret” option is for players who are already familiar with the game, have an idea outside the bounds of what the above two options can do, and want to work with their GM to make the hero they dream of playing. With that option, they just build the hero directly. Between these three options, just about any player can arrive at a hero that is suited just for them.

The next section of the book is the “Moderating the Game” section. This is a large and well-presented chapter with GM-facing rules, advice, and other materials. This section talks about how to run the minions, lieutenants, villains, scenes, environments, etc., as well as giving advice on how to wring the best action scenes out of the system. I felt this section hit the “sweet spot” of being detailed enough to convey what it needed to, concise enough to be accessible, and fulsome enough where it needed to be to give insightful advice for improving the play experience. Definitely a good read for both novice and experienced GMs.

The remaining three chapters are adventure content. The “Archives” chapter contains a lot of pre-made heroes and villains to populate your game world with, and the “Adventure Issues” chapter contains two adventures to challenge your players with. But the star of these chapters is easily “the BullPen” chapter, which offers solid, easy-to-follow, flexible rubrics to help GM’s create action scenes. I was truly impressed with how well-supported creating adventures is in this game; the algebra of balancing and presenting an action scene makes designing your own adventures a snap, even on the fly! There are concise, easy-to-follow rules for creating scenes, enemies, villains, doomsday devices, environments, etc., and it’s all accessible and approachable in ways that I haven’t really seen in a lot of RPG’s. It won’t take much experience with the game before you can quickly create adventures with little trouble and have a good idea of their difficulty and complexity at the table.

Gameplay

So…how does it play at the table, then?

I’ve been very pleased with this system. I’ve played Champions, Mutants and Masterminds, and many other games, but this is the first system that really managed to capture the feel of comic book style superheroics for me, and it did it with a simple, straightforward, and accessible system that’s both easy to teach to RPG newcomers and crunchy enough for veterans.

The genius of the system is that it doesn’t even try to model the specific effects of each super power. The problem with games like Champions has always been that superheroes, by definition, break the rules of reality, so trying to effectively simulate a world where heroes naturally breaking the rules of reality becomes very fragile.

Sentinel Comics RPG solves this in a very clever way that eliminates the complexity. All actions heroes take are classified as one of five things: attacking, defending, boosting, hindering, or overcoming. These actions abstract the in-fiction behavior enough that it gets out of the way while still providing “teeth” to the players’ decisions and tension on the clock as villains enact their plans.

Attacking and defending is about dealing or preventing damage, and are quite straightforward. Attacking with fire uses the same system as attacking with martial arts or a laser; the differences are handled at the fiction layer. This allows the player to “skin” those attacks however they like. If you want to attack that robot by jumping on its back and twisting its head off, you can do that. If you want to attack that robot by melting it with your fire powers, you can do that. And because this all happens at the fiction layer, there are no complicated rules about those weird edge cases that will inevitably come up; your GM handles deciding things like whether your fire powers work in a vacuum or underwater, or whether your psychic blasts work on those AI robots.

Boosting and hindering is about making things harder or easier for your allies and enemies. At first glance, this seems like a minor option, but at the table, it truly shines. This is the mechanism that turns a group of individuals into a superhero TEAM. Again, this is a simple system that is “skinned” based on the player powers. You might hinder that robot by telekinetically wrapping it in chains, or dominating it with your arcane eye, or creating ice under its feet. All these do is create story-relevant bonuses and penalties, but they are significant ones, often meaning the difference between defeat at the hands of the villain and victory using clever teamwork.

Finally, overcoming is the catch-all problem-solving mechanism for anything else the hero does, such as rescuing innocents from a falling building or disarming the villain’s doomsday device. Anything that doesn’t fall under the other actions becomes an overcome, and the players can skin their approaches to problems – and even what problems they want to solve – however it makes sense in the fiction. The power of this was driven home for me the first time I ran a session of the game. A player playing Absolute Zero, a cold-based character, saw the bad guys fling an innocent civilian from high up. The player said, “I use my cold powers to create a deep snow bank for them to fall into!” And it just WORKED. There are no rules for falling damage, catching things, using cold powers to break falls, etc. It’s just “overcoming a problem” – if the player can imagine a comic panel showing the hero solving that problem, they can go for it! Creatively using their powers like this is baked into core of the system, and it feels spontaneous and versatile. Once the action has been chosen, there’s a very simple system for rolling for success. Each hero has a list of powers and qualities, each associated with a die size. The hero chooses one of each type, and then a third based on their current health, and roll them. For instance, Absolue Zero above might have chosen his “d12 Cold Powers”, “d8 Creativity Quality”, and “d8 Green Zone for Health”. The player then rolls those dice, putting them in order. Most effects look at the result of the middle-valued die, but some hero special abilities let you do more, such as attacking with your Max die, or attacking multiple targets with your Min die.

The result determines the outcome. In the case of attacking and defending, the roll is simply the damage – an attack just causes the result as damage, and defend defends that amount from the next attack. For boosts and hinders, every four yields another +1 or -1 on a future die roll. And for overcomes, the value determines whether the overcome is successful or not, and whether or not it creates a “twist”. Knowing when to boost, hinder, attack, or overcome is the core strategy of the game, and it is fiction-first, making it easy for players to reason within.

On the GM side, there are a lot of affordances that make running the game a breeze. There are three “tiers” of enemies – minions, lieutenants, and villains. Minions and lieutenants have simple core rules with ways to customize them; each is represented by a die size, like a d6 Ninja or a d12 Tyrannosaurus, along with a few tactics and special ability notes. These are exceedingly easy to run, allowing you to very quickly model even a large number of enemies fighting the heroes. Villains, on the other hand, are statted out much like heroes, and are more complicated, but they use the same systems that heroes do, and are straightforward to run as a result.

Overall, the game feels very streamlined and quick, which is perhaps the number one reason it is able to capture the feel of comic-book action: minimal down time. Turns go quickly, and everything is abstracted to let players imagine their own fictions, which lets the heroics and dreadful reversals come forward with very little to get in the way. It’s exceedingly slick and easy to run.

But best of all, the fiction-first flexibility allows you to be as superheroic as you want. One of my players had made a character who was a psychic ghost with ties to the Lord of the Dead. In their first episode, they encountered a horde of robots, which I had ruled were immune to their psychic attacks. In a regular game, this would shut that hero down, relegating them to being support at best for the fight. Instead, the player asked if that hero could attempt an overcome action pull the entire scene into the Land of the Dead so that her psychic emanations could affect the robots. I said I’d allow it, and their overcome check succeeded, so I just described the sky turning blackish-green, the temperature plummeting, and everything turning into shadowy mirages of their mortal counterparts. It was a great moment that evoked those double-page spreads in comic books which give real spotlight moments to a hero. Mechanically, it was dead simple to run, didn’t skew the balance of the game, and the system didn’t break a sweat to support it, delivering a massively cool moment that felt like true comic book drama!

Downsides

I have heard a few down sides to the game for players, and I would be remiss not to mention the ones that I think are fair criticisms.

First, there is a concept in some scenes of a “scene tracker”. This tracker goes from green to yellow to red, and this, combined with the heroes’ personal health zones, determines which special abilities they have access to. Early on, when they’re healthy, they can only use the “green” abilities, which are generally the weakest. As the scene progresses and gets more dire, they also gain access to the “yellow” and finally the “red” abilities. One can reasonably object – why can’t my hero just do the red ability first? Do they not know how to do the thing? It’s a fair criticism, but I haven’t found it to be much trouble at the table. Mechanically, it ensures that the stakes ramp up and the action has a better feel. So many of my Dungeons and Dragons fights feel overwhelming and hard at the start and feel like we’re “just mopping up” at the end, which is exactly opposite to what it should be; action scenes should drive toward climaxes. This system achieves that, but it’s fair to say that it does it in an artificial way. Whether this bothers you or not probably depends how much you let it intrude on your collective fiction.

Another criticism I’ve seen leveled at the game is that it doesn’t have much in the way of character advancement. You’re not going to be “leveling up” and getting exponentially tougher and going on tougher and tougher adventures as you advance. While there is a sort of “experience” system in place, I can see why this would be a deal-breaker for someone who really likes advancement. You’re not going to slowly turn into a god. More like, you become a veteran superhero over time, getting more and more adept at using the powers you have. (There are also mechanisms for totally re-building your character, for those story arcs where heroes transform drastically, but they’ll be of similar power.)

Again, while this is a fair criticism, I feel like it comes with a major advantage, too: you don’t have to start out as a wimpy superhero – the whole “fight rats in cellars to gain XP” thing. Right out the gate, you can play America’s Finest Legacy or the Sun God Ra, and be powerful and capable and take on the arch villains, which is kind of how it should be.

Some players unfamiliar with the Sentinel Comics universe may feel hesitant, as it is based on the rather extensive existing lore of the Sentinels of the Multiverse card game and the Sentinel Tactics board game. There are a lot of heroes with long back stories that appear in the game materials, including the Starter Kit. This can be understandably intimidating to people new to the franchise.

Luckily, familiarity with the “Sentinel Comics” lore is not required. Anything you need to know about any given hero or villain in an adventure is minimal and provided in the adventure content, and can almost always be conveyed to players using their analogues in DC or Marvel. “Legacy? Imagine Captain America with the powers of Superman instead of a shield.” And the system does not require the Sentinel Comics universe; it would work perfectly fine for a GM to set the adventures in their own universe design.

Finally, I’ve heard some people feeling a little lost in creating some of their more-out-there superhero concepts. Often, though, this is a case of perhaps taking the powers list too literally. There’s a lot of freedom in the game to skin your powers, and really, all you need to do is get “close” to the power you want, and it works fine. It does take playing the game to understand that, though, so I’d recommend playing at least one session with the pre-generated characters in the Starter Kit before trying to make a character – it’s a lot easier to understand the character creation process once you’ve played.

All told though, I struggle to come up with much in the way of criticisms of this game. None of the three criticisms above have derailed us from playing and having a good time, and even the people who brought up the above criticisms still said they enjoyed the game quite a bit.

Conclusion

Sentinel Comics RPG advances the art of superhero storytelling in RPG’s. It’s fun to play and a breeze to GM, with plenty of support material for players wanting to make their own heroes and GM’s wanting to make adventures to challenge them.

In short, yes, the three years were worth the wait.

PROS:

* Solid, accessible, evocative superhero action.

* Versatile hero creation for random or envisioned heroes.

* Quick gameplay with fiction-first flexibility.* Streamlined affordances make GM’ing a breeze.

CONS:

* Not much in the way of character advancement.

* Some artificial throttling of hero power for purposes of tension-building.

* Pricey at $60 MSRP (PDF may be cheaper, and you can try the Starter Kit for free).

(As of this writing, the core rulebook is not released; my copy was a KickStarter copy, but the book should be available as PDF and hardcover on the Greater Than Games store sometime within the month. In the mean time, the Starter Kit is free to download to get started, which will easily last you six full gaming sessions.)

What does this bring to the table that ICONs doesn’t?

I’ll be honest the 3 year gap is a big negative for me but I’m also not sure if this game is ‘needed’ with Icons and Cortex out there.

If they show solid support for it i’ll give it a second look.

LikeLike

The mechanics basically just sound like Fate, though. How does it differ from that?

LikeLike

I don’t have a huge amount of familiarity with Fate, but as far as I’m aware:

SCRPG shares a lot of design philosophy with Fate – they’re both very narrative-focused. But the mechanical implementations are pretty different.

SCRPG’s die-rolling mechanic (almost) always has you rolling three dice – one for a Power, one for a Quality and one for the GYRO status (we’ll get to that 🙂). For basic actions (attack/defend/boost/hinder/overcome) you pick any Power and Quality you can justify as fitting what you’re teying to do. Heroes also have Abilities which are more powerful than basic actions but more specific and often require a specific Power or Quality.

You do not add the dice. Your result is usually the value of just one of them. For basic actions this is the median value. Some abilities let you use the max value or the min value, or even do something like “Hinder an opponent with your Max die value then attack that opponent with your Min die value”.

GYRO (Green/Yellow/Red/Out) status is determined in two ways. Firstly, the scene ramps up from Green > Yellow > Red as rounds pass. Secondly, a character’s personal GYRO zone is decided by their current health. The GYRO status controls both what GYRO status die you roll and what abilities you can use. Green abilities are always available, Yellow abilities only become available when you reach Yellow, and the most powerful Red Abilities become available when you reach Red status. For example, if the scene is in Yellow and one hero has taken a lot of damage and their personal GYRO zone is in the Red then that hero gets access to their Red abilities and uses their Red status die, while everyone else is only up to Yellow.

The scene tracker is used for action scenes only, and in those scenes the tracker provides a framework that means the action gets bigger and bigger as the scene progresses. It also puts a timer on the scene – if your team haven’t achieved the goal of the scene by the time Red runs out, then you fail that goal and have to deal with the fallout.

SCRPG bakes the concept of “twists” into its Overcome rolls. The most common result is “success with a minor twist” and the GM and player decide between themselves what an appropriate twist might be. It can be mechanical or narrative. For example, if your hero diverts a river to put out a fire, maybe that damages their power armour, or maybe it accidentally destroys the prized car of a local newspaper editor and can expect bad publicity down the road. (The player also has the option of choosing to fail the action rather than take a twist).

SCRPG handles initiative by letting whoever just acted pass to whoever they want (including opponents) until everyone has had one turn and the round ends. (Note that you can pass to everyone on your team first, but that will mean that it’s then all your opponents turn and, once they’ve all acted, they can then start the next round by passing initiative to one of their number – resulting in the entirety of team opponent acting twice before you get to go again).

There’s more differences, but those are the main ones off the top of my head and hopefully it gives some idea how the systems differ.

LikeLike

Re: “Finally, I’ve heard some people feeling a little lost in creating some of their more-out-there superhero concepts.”

Personally I find that Sentinels’ character creation is great for giving you interesting prompts that challenge you to come up with an interesting and fun character. I don’t find that even the constructed method is particularly geared towards starting creation with a character concept already in mind then trying to build that concept. That’s just not its focus.

LikeLike